Sanders and the S Word

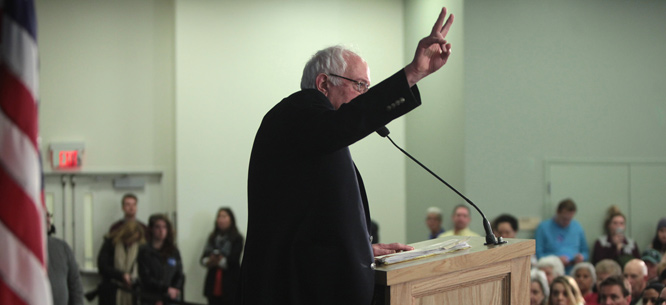

Last November, Bernie Sanders told an enthusiastic audience packed into the largest hall at Georgetown University what “democratic socialism” means to him. He drew largely on the examples of two presidents, a civil rights leader, and a Pope—not one of whom identified himself as a socialist. Sanders praised Franklin Roosevelt for creating jobs and enacting Social Security and hailed Lyndon Johnson for initiating Medicare and Medicaid. He cited Martin Luther King, Jr.’s conviction that true freedom requires economic security. He quoted Pope Francis’s censure of “the worship of money.” Then Sanders repeated his familiar attack on the “billionaire class” and his call for universal health care and an end to tuition at public colleges.

One can easily imagine a liberal stalwart like Senator Elizabeth Warren or Senator Sherrod Brown making the same speech, yet without embracing the “S” word. Why does the white-haired firebrand from Vermont insist on identifying himself with socialism, a political faith that has never been popular in the United States?

I have never met or spoken to Bernie Sanders. So I can only speculate about his reasons. But they probably have a lot to do with the surprising influence of democratic socialists in modern U.S. history and his desire to be part of that long, if largely unheralded, tradition.

Until Sanders, the most popular American socialist was Eugene Victor Debs—a charismatic orator and erstwhile union leader whom Sanders respected so much that, in 1979, he made an earnest audio documentary about him. Unlike his latter-day admirer, Debs ran for president—five times!—as the nominee of an actual Socialist party. He never won more than 6 percent of the popular vote, but Debsian Socialists headed several major unions, did much to organize the broad coalition that almost kept the United States out of World War I, and launched the movement for birth control. Their prominence in social movements spurred progressive officeholders like Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson to advocate economic and political reforms, in part to stop the radicals from gaining more support from the discontented.

In the early 1960s, Sanders joined the Young People’s Socialist League (“Yipsel” to aficionados of the left) as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago even though its parent party was nearly moribund. The Socialists had even stopped running their own candidates for president; liberal Democrats had adopted some of their proposals (like Social Security and protection for union organizing) and captured nearly all of their voters.

But several prominent Americans who had once been active Socialists continued to advance the party’s ideals. Walter Reuther headed the United Auto Workers, perhaps the nation’s most powerful union and a key financial supporter of the civil rights movement. Both A. Philip Randolph, who inspired the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and Bayard Rustin, the organizational mastermind behind it, had also been Socialists. The man who gave the unforgettable, final speech at that march of a quarter-million people had never been a card-carrying socialist, But Martin Luther King, Jr. did often express his admiration for the welfare states of Scandinavia and publicly advocated “a massive program by the government” to aid working people of all races. Echoing a familiar socialist theme, King argued that the only way to defeat racism would be to forge a class alliance of African Americans with poor whites so “confused . . . by prejudice that they have supported their own oppressors.” Meanwhile, Michael Harrington, a rising leader in what remained of the Socialist Party, became famous for writing The Other America, the eloquent book that inspired the War on Poverty.

Thus, for the young Bernie Sanders, to embrace socialism meant joining an enduring tradition even if the organization of that name in the United States was slowly dying. Under the name of Social Democracy, that tradition was prospering throughout northern and western Europe. It was also thriving in Israel, governed since independence by the Labor Party; Sanders worked on a kibbutz there after college.

In the black freedom and antiwar movements he joined back home, hardly anyone objected to the ideals of socialism. But few activists still believed in Debs’s dream that Americans would someday come to their common senses and elect socialists to govern the nation.

In a way, Bernie Sanders has devoted his long political career to proving them wrong. First as mayor of Burlington, then as congressman and senator from Vermont, and now as a surprisingly competitive candidate for president, he has preached the same gospel as did Debs and Randolph, Harrington and King: the tiny elite which Franklin Roosevelt called the “economic royalists” dominates both the workplace and the marketplace; its wealth and power subverts democracy and fuels inequality of all kinds. Sanders appropriates the words and legacy of FDR and LBJ to demonstrate that his socialism is as American and as legitimate as their liberalism—only more consistent in its critique and more uncompromising in pursuit of its goals.

The ease with which Sanders talks about socialism today is also indebted to the conservatives he despises. The grassroots right turned the word into a ubiquitous accusation against the president he hopes to succeed. Since he came into office, Barack Obama’s ideological adversaries have called him many things. But “socialist” heads the list. A quick search for the president’s name and the “S” word turns up thousands of images of Obama with hammer and sickle, Obama reviewing troops in Red Square, Obama embracing Karl Marx, and so on. Unsurprisingly, many young people with no memory of the Cold War reflected that if a president they like is a “socialist,” perhaps that’s not such a bad thing after all. Bernie Sanders has benefited from that linguistic irony.

In any European nation, to call someone a socialist is not a slur but a simple political fact. By running as a Democrat, Sanders has paradoxically gained more attention for socialism and its history in the United States than if he had remained an independent party of one, known mostly to his fellow leftists. He remains a long shot to win the presidency. But if he loses, he can take solace in the response Debs often made to people who asked why they should “throw away” their votes on a radical: “better to vote for what you want and not get it than to vote for what you don’t want and get it.”

Michael Kazin is co-editor of Dissent.

No comments:

Post a Comment